Food Coloring

The Production and Influence of Food Coloring

by Mallory Schiavo

Green cheese? Black

birthday cake? What about purple pickles? I would be willing to bet that none

of these food options sound particularly enticing to you. That is because color

plays a crucial role in determining which foods appeal to us and which do not. We

have come to expect our foods to be certain colors (even when they are not naturally

so) and any deviation from our expectations averts our appetite. It is this

context that makes food coloring so influential. We rely on both natural and

synthetic dyes to create what we want, causing changes in their production to greatly

affect our diets. Conversely, changes in what we want to consume significantly impact

food dye production.

(WordPress.com)

Natural Dyes

Natural food coloring has been used since the days of ancient civilizations to enhance people’s eating experiences. “Natural” coloring refers to dyes that are made from materials found in nature, such as minerals, plants, insects, and animals (Lakshmi 87). While all coloring is derived from some original natural source, natural coloring is not chemically synthesized like synthetic coloring is. For example, saffron is a spice harvested from the saffron crocus flower that has been used to give food a yellow color since at least the 8th century B.C.E., when Homer mentions it in The Iliad (Burrows 394). The process of turning saffron into a coloring is extremely laborious, given that it must be done by hand. This involves each small, red stigma of the flower being plucked from the rest of the plant and then dried before use. Because of their more difficult methods of production, natural dyes have been reserved for upper classes throughout history. (Even today, saffron is increasingly more expensive and hard to come by, earning it the nickname “red gold.”) It is natural colorings such as saffron, as well as paprika, turmeric, beet extract, and flower petals, that earlier civilizations depended on to add desired color to food (Burrows 87). Such limited sources narrowed food coloring choices to red, yellow, green, blue, and brown, with little possibility for varying shades (Schriver 154). This dependence on nature lasted well into the modern age, as it was not until the 19th century that synthetic dyes were introduced.

Saffron crocus flowers.

(Amazon.com)

Saffron stigmas extracted for spice.

(TheSpiceHouse.com)

Synthetic Dyes

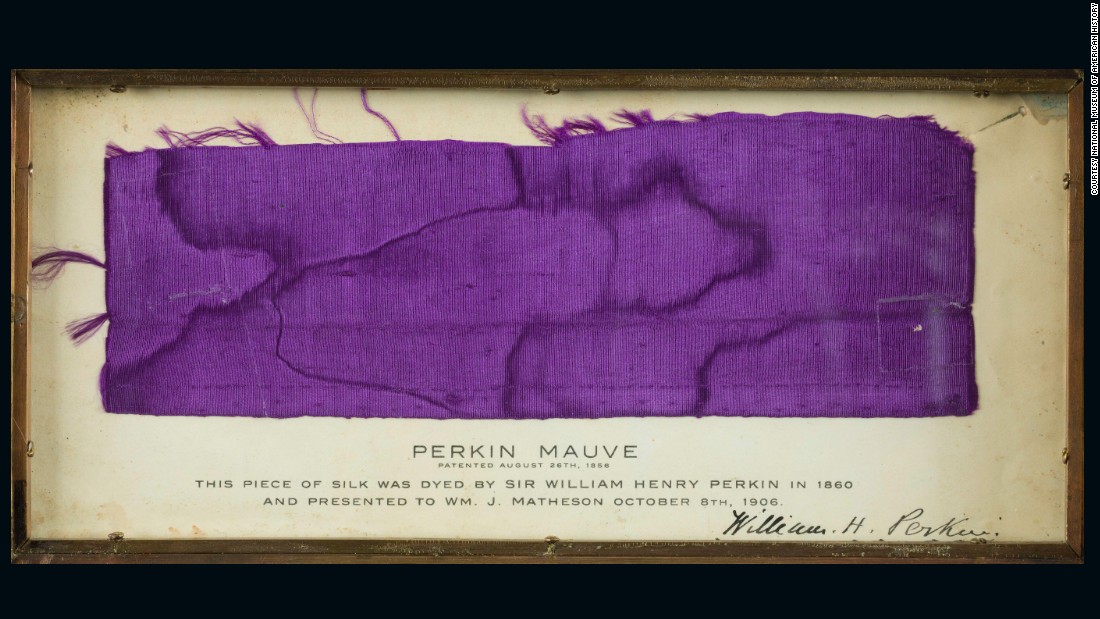

In 1856, English

chemist Sir William Henry Perkin accidentally created the first synthetic dye,

mauveine. While attempting to synthesize the chemical compound quinine to form

an anti-malarial drug, he ended up creating a purple dye instead. Though he

failed in his original endeavor, Perkin recognized the value of his accidental

discovery and quickly patented the dye. Initially known as aniline purple, mauveine (or mauve) was produced

from the organic compound aniline, which was derived from petroleum or coal. This

serendipitous discovery forever changed food coloring (as well as the textile

industry), for it led to the creation of hundreds of new synthetic dyes known

as “coal-tar colors.” These new chemically produced colors were less difficult to create, less expensive, and better at retaining color (Burrows 396). The achievement of synthetic dyes

has granted food manufacturers a plethora of color possibilities, from brightly

colored candy to an array of breakfast cereals. In addition, cheap production

costs and widespread use have expanded food coloring to the common person’s

consumption, as opposed to the earlier days of expensive natural dyes.

William Henry Perkin, creator of first synthetic dye.

(ScienceHistory.org)

Silk Perkin dyed with mauve invention.

(CNN.com)

Dye Regulations

However, this new age

of food dyes began to face limitations as government regulations were enacted. In

the U.S., the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act banned the sale of any so-called

“adulterated” food. This included any food with added ingredients that were

harmful to consumers’ health. The act also prohibited coloring food as a means

of hiding poor quality. In order to investigate which food dyes were harmful,

the Bureau of Chemistry gradually tested all 80 that were in use. By 1938, the

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved 15 synthetic dyes for use in

food. In the same year, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was passed, providing

more specifications on food dye regulation. It held that all synthetic dyes in

food had to be listed by the FDA as harmless and that each batch of coloring required

testing and certification before use.

Public Opinion

In the decades that have

followed, food coloring has faced changes in both regulation and public

opinion, shaping the way we eat. While the inception of synthetic food dye

caused much excitement (mainly on the part of manufacturers), its progression has

stirred a great deal of controversy regarding its safety. For example, in the

1950s, cases of children falling ill from Halloween candy and popcorn sparked

public alarm. This resulted in three synthetic dyes (Orange 1, Orange 2, and

Red 32) being retested for harmlessness. When they were shown to cause serious health defects in lab animals, they were removed from the FDA approval list

(Burrows 400). Similar instances have occurred over time and with each new

study, food scare, dye removal, etc., the public has grown more wary of synthetic

food colorings. The significance of public sentiment is exemplified by the absence

of red M&M’s from 1976 to 1987. When the FDA banned Red 2 in 1976 due to

inconclusive safety tests, the Mars manufacturing company decided to

discontinue the beloved red-colored M&M, despite it not using that particular

dye. Mars wanted to ensure that consumers were not turned away from buying

M&M’s just from the sight of red food coloring. So, it replaced the red

M&M with orange, until public fear died down and the red was reintroduced,

giving us the six-colored mix we enjoy today.

(Nuts.com)

Currently, public attitude

seems to be continuing on the trend away from synthetic food colorings. Health

experts, doctors, news articles, and next-door neighbors have joined together to

warn parents against feeding their children synthetic, or commonly known as “artificial,”

dyes. A recent report by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI)

found that the nine synthetic food dyes currently used in the U.S. are likely carcinogenic, cause hypersensitivity and behavioral problems, and are not tested thoroughly enough (Potera A428). Understandably, public concern is in

abundance and it is leading more companies to change their ingredients, such as

the recent announcement that General Mills will no longer use artificial dyes

in its popular cereals (Lucky Charms, Trix, etc.). Such changes demonstrate the

way in which food manufacturers are bending to meet consumers’ desires. This has

led to a global increase in the natural food coloring market, which has already

reached $1 billion (Lakshmi 88). In all, if public opinion continues to favor

natural colorings, synthetic dyes may be doomed. A return to the days of exclusively-natural

food dyes might very well be in our future. Only time will tell.

Bibliography

Burrows, Adam. “Palette of Our Palates: A Brief History of Food

Coloring and Its Regulation.” Comprehensive

Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, vol. 8, issue 4, 2009, pp.

394-408. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2009.00089.x. Wiley

Online Library Accessed 23 May 2018.

Lakshmi, Chaitanya. “Food Coloring: The Natural Way.” Research Journal of Chemical Sciences,

vol. 4, no. 2, 2014, pp. 87-96. www.isca.in/rjcs/Archives/v4/i2/15.ISCA-RJCS-2014-007.pdf.

Accessed 23 May 2018.

Potera, Carol. “Diet and Nutrition: The Artificial Blues.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol.

118, no. 10, 2010, pp. A428. www.jstor.org/stable/20778567. JSTOR. Accessed 23

May 2018.

Schriver, Dorothy. “A Century of Color.” The Science News-Letter, vol. 70, no. 10, 1956, pp. 154-155. www.jstor.org/stable/3937545.

JSTOR. Accessed 23 May 2018.

I love this post. The hook grabs me and from there I found myself not wanting the piece to end. The topic is creative and very relatable. The photos are clever and fitting and it seems like writing that everyone should read. I reread the post a couple times and still struggle to nitpick something I would change substantially, the post feels very close to complete. Maybe I'll just say that sometimes black chocolate cake is tasty so I don't know about that part of the intro. Excellent work.

ReplyDeleteMallory, This is a really interesting topic to research and I enjoyed reading it. I find it interesting to read the trends you point out of the M&M color changes as well as current move towards natural food dyes. I think it would add to your work if you break up your paragraphs into categories so that It feels less like an essay and more like a blog. Great Job!

ReplyDeleteReally interesting topic and blog post! I enjoyed the bit about red food coloring and M&Ms since that was totally new information for me. It would be nice to have subheadings to label each part of your entry so readers know the different topics you address.

ReplyDeleteWho knew that food color was so interesting! I found this post fun to read because most of us, if not all of us can relate to this. We all eat food and some of us base what we eat off colors. For example, picky eaters like to eat "yellow foods" and vegetarians eat "greens". I really enjoy the pictures you included in your post however, I think a fun and educating food coloring video would be successful in this piece so we can see the process of how they can alter the color of foods. Overall, I really enjoyed reading this piece. It was fun and educating to read.

ReplyDeleteMallory, You have a very nice post here -- it's interesting, well written, and informative. I have a couple of suggestions: first, if you want to mention "coal tar colors" you should probably mention that coal tar is the material from which Perkin created the first synthetic mauve. Otherwise it doesn't make much sense. 2) in your second sentence on the government regulations, a better word -- "included" -- might make more sense than "entailed." Any food with additive dyes fell under the regulation, and entailed isn't the word you want there. "Delisted" is a very specific word which applies to the stock market -- what you mean is "banned" or "forbade the use of" Red Dye #2. "Re-added" isn't a word -- you might want to use something like "reappeared" instead.

ReplyDeleteConsumers' "wants" might be better phrased as "Consumers' desires". These are all nit-picky points, however -- your comparison of the natural dyed Trix and the synthetic food coloring used originally was very effective as an illustration. I liked the purple pickle too! One other point I'll mention -- and I know that you were being very careful to quote the phrases you used from your sources -- but usually when something is stated and you could rephrase it in your own words, you should put it in your own words and then footnote the source for the information. When you directly quote something/someone, you usually are doing so because a particular point is being made with the language used, rather than just taking a descriptive passage and quoting it. So “severe health problems in lab animals” doesn't have to be something directly quoted from the author -- you can simply paraphrase this in your own words and then footnote the source. The importance is not the precise wording of the phrase, but rather, simply the fact that the dyes produced physiological problems or severe conditions in laboratory animals. But all of that being said, I very much enjoyed your post!